Dzięki uprzejmości dr Bogumiły Żongołłowicz, na koniec Roku Pawła Edmunda Strzeleckiego udostępniamy przetłumaczony na język angielski rozdział „Hip, hip, hura!” pochodzący z książki Konsul. Biografia Władysława Noskowskiego. W rozdziale tym została opisana historia obchodów stulecia nazwania Góry Kościuszki, a także losy tablic upamiętniających to historyczne wydarzenie.

Hip, Hip, Hurray!

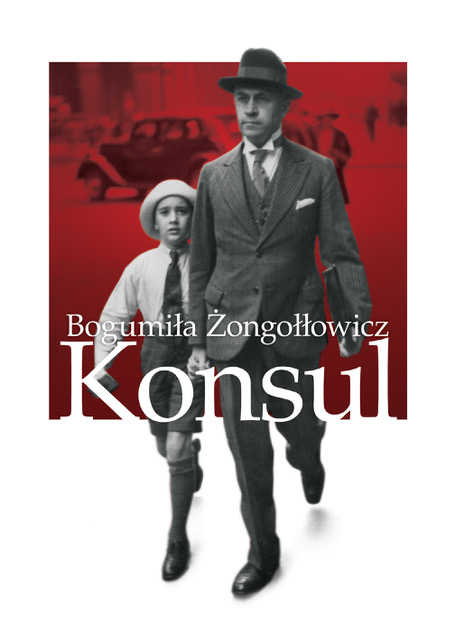

Excerpted from Konsul [The Consul] by biographer Bogumiła Żongołłowicz, about the life of Władysław Noskowski, translated by Alexandra Chciuk-Celt, all rights reserved.

Translator’s note: Andrzej Tadeusz Kościuszko (1746-1817), pronounced kush-CHOOSH-kuh, was a Polish patriotic hero and military engineer who fought the Russians and Prussians during the partitions of Poland-Lithuania and the British in the American Revolutionary War. His name was frequently misspelled Kosciusko and Kosciuszko.

The Second World War saw the hundredth anniversary of the first recorded ascent of Mount Kosciuszko (spelled Kosciusko until 1997) by the outstanding Polish explorer, traveller, and scholar Paweł Edmund Strzelecki (1797-1873). Although he only remained in Australia for four years, Strzelecki nevertheless entered the country’s history. Mount Kosciuszko (2228 meters above sea level), which he climbed, surveyed, and named, is the highest point on the continent, located in the Australian Alps.

The close-knit group of people interested in the centenary celebrations included Consul Noskowski as well as Herbert John Lamble, who ran the Hotel Kosciusko, which the Noskowskis would frequent. The one-storied 250-bed building of stone and wood was constructed with State money in 1909. Lamble wanted it to equal Swiss hotels in stature. The hotel burned down in 1951.

While in Europe in 1933, Lamble combined business with pleasure and visited Kraków so as to familiarise himself with information about Tadeusz Kościuszko. When asked whether his own compatriots knew the origin of the mountain’s name, he said: “… many Australians believe that word originated… with the Australian aborigines. This is why I decided to make my hotel some type of propaganda for that great name. In Kraków I found the Kościuszko coat of arms, which I plan to place up front… and on the stationery as well …. I also want to have my hotel feature booklets about who Kościuszko was, and an appropriate plaque. [Pozdrowienie z dalekiej Góry Kościuszki, Ilustrowany Kuryer Codzienny (Illustrated Daily Courier), No. 45, 1933, p. 2.]

Lamble also intended to install a commemorative plaque and even a bronze statue atop Mount Kosciusko, similar to the Kościuszko statue on Kraków’s hallowed Wawel Hill, and “surrounded by a series of figures representing great Australian discoverers. Of course one of the primary positions would be occupied by that of Count (sic!) Strzelecki,” he said. “I am under the impression that faraway Australia and Poland could reach an understanding in many fields, since they have so many similar traditions.” [Ibid.]

Bogumiły Żongołłowicz)

Consul Noskowski also spoke about a statue on his visit to Poland, albeit one of Strzelecki. At that time he commissioned Wojciech Kossak to paint the explorer’s portrait astride a horse; it was never painted, probably because the war broke out. A gigantic Strzelecki monument, a gift from the Polish nation, was put up in the small town of Jindabyne for the bicentenary of the discovery of Australia. he bronze creation was effected by artist Jerzy Sobociński, the casting by the Technical Devices Authority in Gliwice, Poland.

Florence Taylor, Australia’s first female architect, was planning a Kosciusko Ball at the “Trocadero” dancing establishment. An art-deco construct which could hold two thousand persons opened just as the country was emerging from a recession and offered some Hollywood-style splendor. On Friday and Saturday nights it was possible to meet well-known actors, popular journalists, club presidents, politicians, thrill-seeking tourists, and most of all, Sydneysider dance enthusiasts. A fancy dress ball in such a site would have proved most profitable, but once again, the war reshuffled everyone’s priorities.

Lamble, Noskowski, and Taylor joined the organising committee celebrating the centenary of the scaling of Mount Kosciusko. Lamble became the secretary, and the director selected was the philosopher and pedagogue Francis Anderson. As the times were deemed inappropriate for frolic, it was decided to keep the events low-key—the unveiling of a commemorative plaque financed by monies from a public collection.

The founders list from 15 December 1939 to 30 June 1940 finalised at an amount of seventy pounds three shillings and ten pence. It was opened by the Kooya Committee of Historical Research, which was responsible for the contents inscribed upon the plaque, by payment of one pound and one shilling, i.e. one guinea. The list also contains many well known personages in the world of culture, politics, and business, such as Hugh Denison and his wife, as well as Henry Manning, and institutions and organisations, including the Royal Australian Historical Society, the Cooma Ski Club, the Kosciusko Snow Revellers Club, the Ski Council of NSW, as well as schools such as the Duntroon Public School and Scots College.

The Arts Club of Sydney actively participated in the collection thanks to its chairman Florence Taylor and princess Harriet Radziwill, the widow of Stewart Dawson, a very rich jeweller and real-estate potentate. Harriet obtained the title by marrying Michal Radziwill in London—“supposedly a penniless carouser,” as Noskowski wrote in a letter to L. Paszkowski on 31 December 1967 [source: author’s files]. She gave him a fortune and came to Australia in order to escape Nazi bombardment. “She told me she always wanted him to join her here, but he refused. She went back to London after the war.” [Ibid.]

The Old Fashioned Musical Evening Florence organized in her home-cum-office and the Novelty Afternoon Tea Party at the “Romano” Restaurant yielded over sixteen pounds. Princess Radziwill added five pounds and five shillings.

On Thursday, 15 February 1940, the centenary of the discovery of Mount Kosciusko, a commemorative plaque was attached to the granite rock at the peak. This was performed by George Day, manager of the Charlotte Pass shelter, along with his workers. The unveiling ceremony was postponed from Thursday to Saturday for logistical reasons: it was a day off from school and work. Numerous people from Sydney professed an interest in participating in the event, and they had to be transported, fed, and lodged. Deciding whether to include children and young people was a pedagogical matter.

The inscription on the main plaque unveiled by Consul Noskowski and his wife reads as follows:

“From the valley of the Murray River the Polish explorer Paul Edmund Strzelecki ascended these Australian Alps on 15th February 1840. A ‘pinnacle, rocky and naked, predominant over several others, was chosen by Strzelecki for a point of trigonometrical survey.’ ‘The particular configuration of this eminence, he recorded, ‘struck me so forcibly by the similarity it bears to a tumulus elevated in Krakow over the tomb of the patriot Kosciusko, that, although in a foreign country, on foreign ground, but amongst a free people, who appreciate freedom and its votaries, I could not refrain from giving it the name of Mount Kosciusko.”

Translated from L. Paszkowski, Polacy w Australii i Oceanii 1790-1940 (Poles in Australia and Oceania 1790-1940), Toruń-Melbourne 2008, p. 151.

Below that a second, significantly smaller plaque installed sometime later noted as follows:

“This commemorative plaque was unveiled by the Consul General of the Republic of Poland for Australia, New Zealand and Western Samoa, Ladislas Adam de Noskowski Esq. on the 17th February 1940.” [Ibid.]

The ceremony’s chief dignitary was NSW Crown Prosecutor Henry Manning, representing the State government in the absence of the Prime Minister, and some four hundred other persons participated. The snowy mountain massif glittered in the sun from the morning. Above the crowd was a group of shepherds in stockings and sombreros from beyond the border with Victoria; it had taken them three days to conquer many miles of difficult terrain on horseback. Never before had the Australian Alps seen such a numerous assemblage. Only half as many people had attended the first Mass read atop the mountain 23 February 1913. (See A Unique Centenary, Cooma Express, 26 February 1940, p. 1.)

Over a hundred pupils from schools in Berridale, Cooma, Jindabyne, Kalkite and Wheatfield who had contributed pennies and halfpennies to the collection sang “Advance Australia Fair”, the Polish and British national anthems, and the march “Poland You Will Rise Again”, composed specially for this occasion by Florence Brigg-Cooper of Annandale in Sydney. [Ceremony. Centenary Tablet. Sydney Morning Herald, 19 February 1940, p. 13.]

Our hearts go out to Poland and her folk across the sea,

This sunny land Australia soon will help set them free.

They proved their dauntless courage, when they suffered for us all,

The very most that we can do, will still be far too small!

So lift our voices every one and join in the refrain,

“Poland you will rise, you will rise again.”

There is money needed sadly, so we now appear to you.

Please give us your pounds or shillings and we’ll take your pennies too.

We know that you’re good Australians and will do your level best,

If you supply the needful, we’ll see to all the rest.

So lift our voices every one and join in the refrain,

“Poland you will rise, you will rise again.”

Consul Noskowski summarized the ceremony events with the following words:

“Nothing was more significant in present world struggle than that, while the Germans were busy pulling down every monument they could find of that great champion of liberty and freedom, the children of Australia were building up another monument.” [Ibid.]

“Hip, hip, hurray!” resounded three times as the adults saluted the children at the end of the official portion, which was followed by refreshments at the Kosciusko Hotel. Participants included Beatrice and Władysław Noskowski, Henry Manning and his daughter, Herbert Lamble, Florence Taylor and Florence Brigg-Cooper. Francis Anderson was absent due to illness. An unexpected but welcome guest was Sydney archbishop Norman Gilroy, a guest of the hotel at the time.

In the name of the Władysław Sikorski government in exile, Minister A. Zaleski transmitted his thanks to Noskowski for his “efforts and propaganda activities for Poland in Australia, and especially for the collection work for the funding of the ceremonial plaque.” [Letter fromZaleski to W. Noskowski dated 20 March 1940 (the author’s files).]

The first vandalisations took place during the consul’s lifetime. “Until 1965 it was possible for an automobile to drive from Charlotte Pass almost to the peak of Mount Kosciusko,” Krzysztof Kleiber, former Embassy secretary, explained by letter dated 4 February 2013 to the author… “Each one had a hammer and other precision tools aboard, hence the ‘vandalisation’ problem. A pocket knife would not have done the job.” [Author’s files.]

In 1997 Kleiber saw the plaques while touring Australia with his wife. Shortly thereafter they had to be removed by the authorities of the Kosciuszko National Park, as he did not find them on his 2004 climb of Mount Kosciuszko upon his arrival to work at the Embassy of the Republic of Poland in Canberra. He attempted to find them due to their landmark value as well as the time and circumstances of their unveiling and did not desist in his efforts until he “discovered” them in some shack on the park grounds and transported them to the embassy building—or rather dragged them, as the larger one weighed over seventy kilograms. The initial consideration was to return them to their original spot, but it soon proved overly difficult to effect. Another idea was to wall them into the Strzelecki monument in Jindabyne. Upon repairs, they were exhibited in the lobby of the embassy in the hope that they might someday return to the peak.

Author’s note: I broached this subject in an interview with SBS Polish Radio 30 January 2017 with the firm conviction that this “someday” might now be upon us, as the Sejm parliament of the Republic of Poland had designated that year as Tadeusz Kościuszko Year.

O książce

Książka Konsul. Biografia Władysława Noskowskiego opowiada historię dziennikarza, krytyka muzycznego, hollywodzkiego aktora, sekretarza Jana Ignacego Paderwskiego, a w latach 1933–1945 pierwszego polskiego honorowego konsula generalnego RP w Australii, Nowej Zelandii i Samoa Zachodnim. Książka została wybrana najlepszą publikacją polskojęzyczną z historii polskiej dyplomacji w konkursie organizowanym przez Ministerstwo Spraw Zagranicznych w 2017 roku.

Więcej o książce na stronie internetowej autorki TUTAJ.

Źródło: Bogumiła Żongołłowicz (All rights reserved)

Zdjęcie tytułowe: Obchody stulecia nadania nazwy Mount Kosciusko (Mount Kosciuszko). Ceremonia odsłonięcia pamiątkowej tablicy na Górze Kościuszki, 17 lutego 1940 (archiwum Bogumiły Żongołłowicz)

Artykuł „O odsłonięciu tablicy na Górze Kościuszki” jest dostępny na licencji Creative Commons Uznanie autorstwa 4.0 Międzynarodowa. Pewne prawa zastrzeżone na rzecz Bogumiły Żongołłowicz (tekst i zdjęcia), Alexandry Chciuk-Celt (tłumaczenie na język angielski), Portal Polonii w Wiktorii (tekst), Federacji Polskich Organizaji w Wiktorii (tekst). Utwór powstał w ramach zlecania przez Kancelarię Prezesa Rady Ministrów zadań w zakresie wsparcia Polonii i Polaków za granicą w 2023 roku. Zezwala się na dowolne wykorzystanie utworu, pod warunkiem zachowania ww. informacji, w tym informacji o stosowanej licencji i o posiadaczach praw.